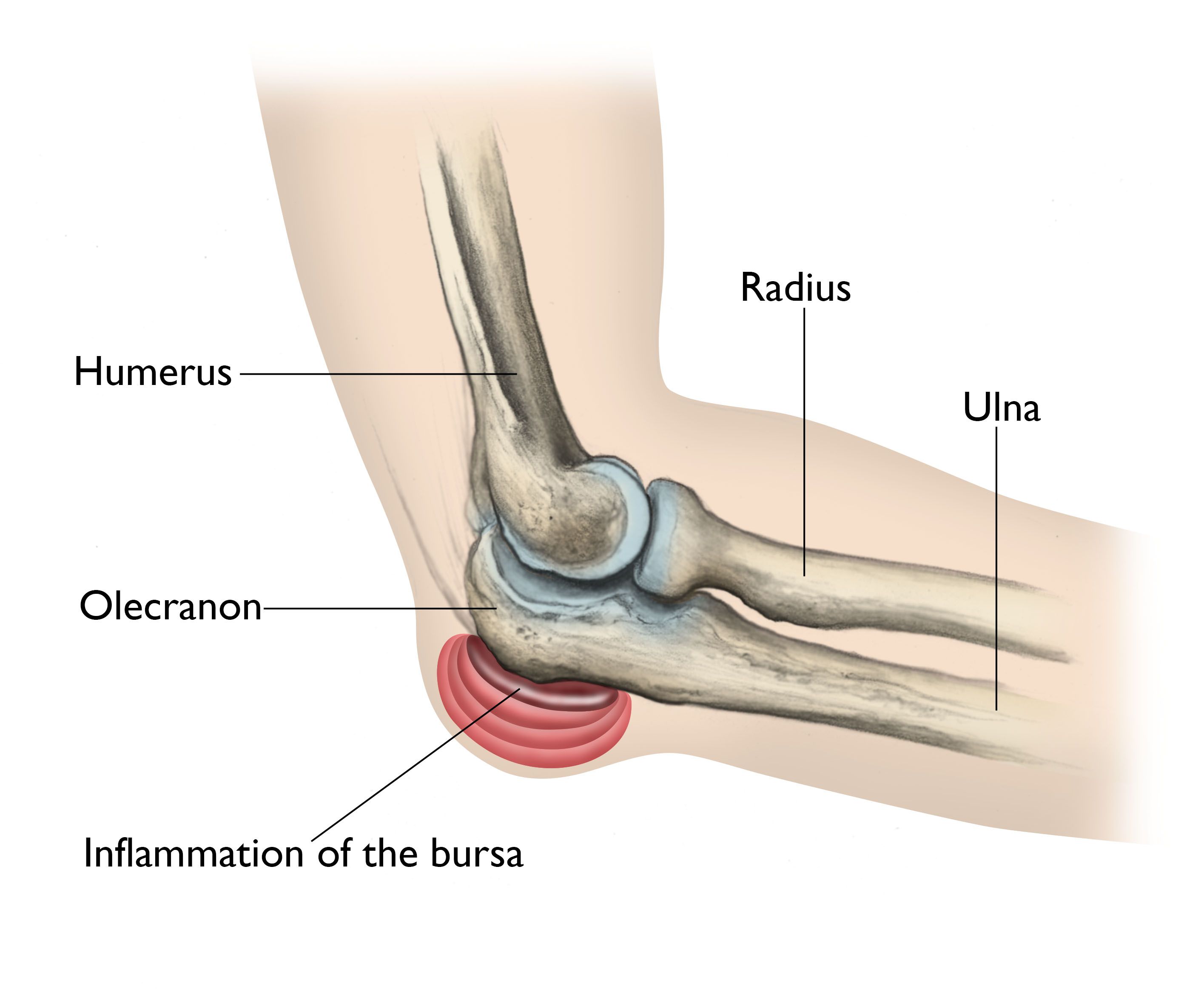

Elbow bursitis occurs in the olecranon bursa, a thin, fluid-filled sac that is located at the boney tip of the elbow (the olecranon).

There are many bursae located throughout the body that act as cushions between bones and soft tissues, such as skin. They contain a small amount of lubricating fluid that allows the soft tissues to move freely over the underlying bone.

Normally, the olecranon bursa is flat. If it becomes irritated or inflamed, more fluid will accumulate in the bursa and bursitis will develop.

Elbow bursitis can occur for a number of reasons.

Trauma. A hard blow to the tip of the elbow can cause the bursa to produce excess fluid and swell.

Prolonged pressure. Leaning on the tip of the elbow for long periods of time on hard surfaces, such as a tabletop, may cause the bursa to swell. Typically, this type of bursitis develops over several months.

People in certain occupations are especially vulnerable, particularly plumbers or heating and air conditioning technicians who have to crawl on their knees in tight spaces and lean on their elbows. Certain athletic activities may also prompt the development of olecranon bursitis, such as long holds of the plank position.

Infection. If an injury at the tip of the elbow breaks the skin, such as an insect bite, scrape, or puncture wound, bacteria may get inside the bursa sac and cause an infection. The infected bursa produces fluid, redness, swelling, and pain. If the infection goes untreated, the fluid may turn to pus.

Occasionally, the bursa sac may become infected without an obvious injury to the skin.

Medical conditions. Certain conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and gout, are associated with elbow bursitis.

Swelling. The first symptom of elbow bursitis is often swelling. The skin on the back of the elbow is loose, which means that a small amount of swelling may not be noticed right away.

Pain. As the swelling continues, the bursa begins to stretch, which causes pain. The pain often worsens with direct pressure on the elbow or with bending the elbow. The swelling may grow large enough to restrict elbow motion.

Redness and warm to the touch. If the bursa is infected, the skin becomes red and warm. If the infection is not treated right away, it may spread to other parts of the arm or move into the bloodstream. This can cause serious illness. Occasionally, an infected bursa will open spontaneously and drain pus.

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your arm and elbow.

X-rays. Your doctor may recommend an x-ray to look for a foreign body or a bone spur. Bone spurs are often found on the tip of the elbow bone in patients who have had repeated instances of elbow bursitis.

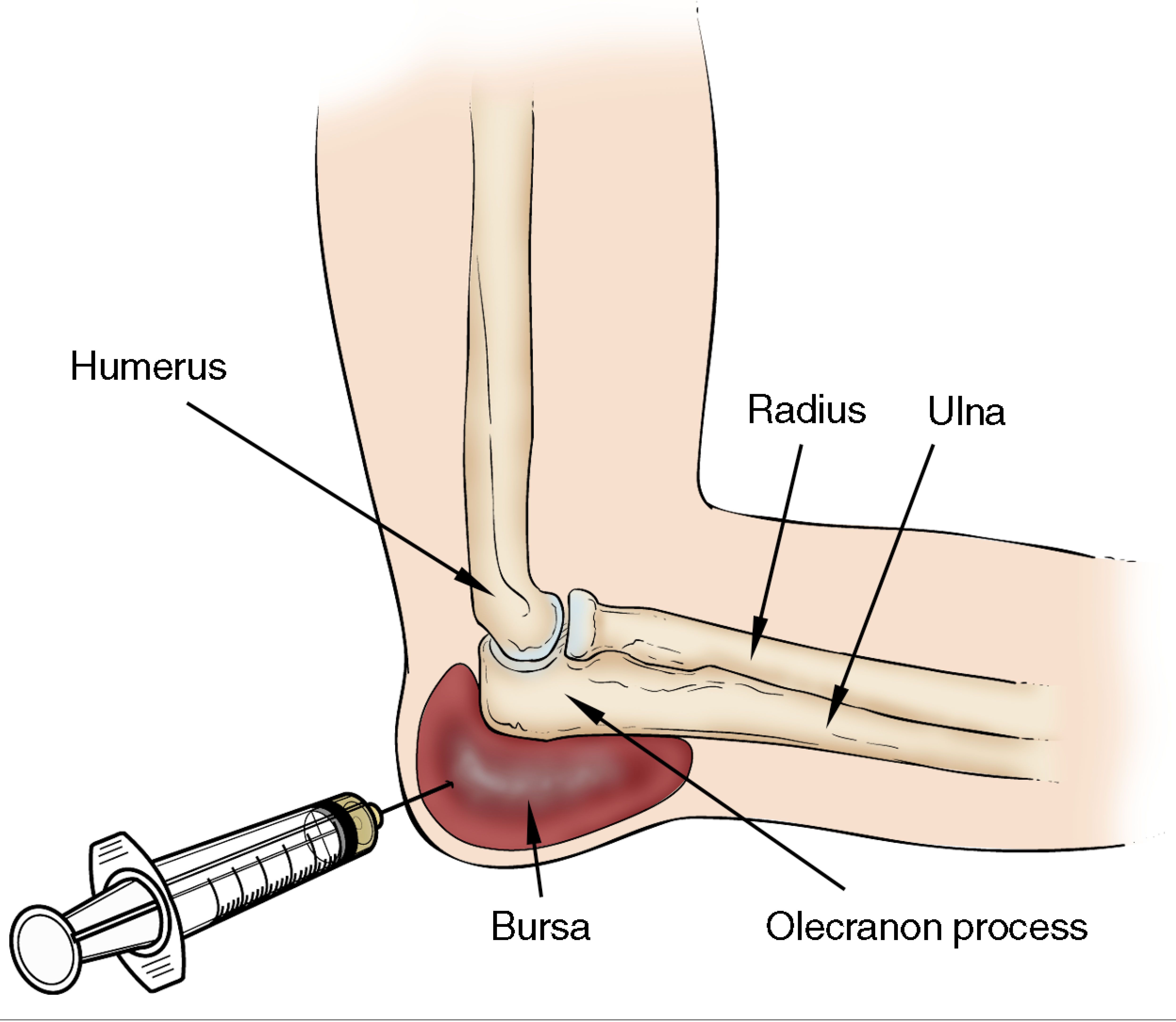

Fluid testing. Your doctor may choose to take a small sample of bursal fluid with a needle to diagnose whether the bursitis is caused by infection or gout.

If your doctor suspects that bursitis is due to an infection, he or she may recommend aspirating (removing the fluid from) the bursa with a needle. This is commonly performed as an office procedure. Fluid removal helps relieve symptoms and gives your doctor a sample that can be looked at in a laboratory to identify if any bacteria are present. This also lets your doctor know if a specific antibiotic is needed to fight the infection.

Your doctor may prescribe antibiotics before the exact type of infection is identified. This is done to prevent the infection from progressing. The antibiotic that your doctor prescribes at this point will treat a number of possible infections.

If the bursitis is not from an infection, there are several management options.

If swelling and pain do not respond to these measures after 3 to 6 weeks, your doctor may recommend removing fluid from the bursa and injecting a corticosteroid medication into the bursa. The steroid medication is an anti-inflammatory drug that is stronger than the medication that can be taken by mouth. In some patients, corticosteroid injections work well to relieve pain and swelling. However, some patients do not have any relief of symptoms with corticosteroid injections.

Surgery for an infected bursa. If the bursa is infected and it does not improve with antibiotics or by removing fluid from the elbow, surgery to remove the entire bursa may be needed. This surgery may be combined with further use of oral or intravenous antibiotics. The bursa usually grows back as a non-inflamed, normally functioning bursa over a period of several months.

Surgery for the noninfected bursa. If elbow bursitis is not a result of infection, surgery may still be recommended if nonsurgical treatments do not work. In this case, surgery to remove the bursa is usually performed as an outpatient procedure. The surgery does not disturb any muscle, ligament, or joint structures.

Recovery. Your doctor will apply a splint to your arm after the procedure to protect your skin. In most cases, casts or prolonged immobilization are not necessary.

Although formal physical therapy after surgery is not usually needed, your doctor will recommend specific exercises to improve your range of motion. These are typically permitted within a few days of the surgery.

Your skin should be well healed within 12 to 16 days after the surgery, and after 3 to 4 weeks, your doctor may allow you to fully use your elbow. Your elbow may need to be padded or protected for several months to prevent reinjury.